How does the brain learn and truly absorb the information it receives? The brain learns through a process of Sequencing: putting information into the right order; Abstraction: making sense of that information; and Organization: using the information to form thoughts. When the brain completes these three steps of processing information, this is called Integration.

The term “integration” is a way of saying the brain has learned something. This may be input from the classroom, or input from life. A child can learn how to add and subtract in the classroom. The child can also learn through life experience that touching a hot stove can burn the skin and cause pain. No matter the source of the information, once it is input and integrated, the brain understands the information it has been fed.

How does the brain, this remarkable organ, take in the information it receives, make sense of it, and use it to create and do incredible things? And what happens when something goes wrong along the way? Is there a way to assist the brain in understanding and absorbing information?

Answering these questions begins with knowing how the brain learns, or the steps we take in processing information. The three steps of the brain’s unique learning formula (sequencing, abstraction, and organization), also provide clues where there are learning difficulties. These clues can ensure we offer children with learning problems the right kind of help.

How Does the Brain Learn: Sequencing

What kind of problems might be spotted as the child learns information? A child might, for example, have a problem with sequencing. If the child has a consistent weakness in this area, a learning difficulty or disability might be suspected. A child may have trouble learning to count, for instance. This might suggest the child has trouble sequencing numbers: putting them in order.

Confirmation that the difficulty has to do with sequencing might come when the child then has trouble learning the correct order of the letters of the alphabet, or the months of the year. When one looks at all the difficulties the child has, and sees they are about placing information into the correct order, two things become clear:

- The child’s brain has a problem with processing information

- The specific neurological (brain) problem is sequencing: putting information in order.

How Does the Brain Learn: Abstraction

Once the brain has the information sorted into the right sequence, it’s time to understand the meaning of the information (abstraction). Most children with learning difficulties have no serious problem with this part of learning. Abstraction is about things like understanding symbols (for example, a stop sign), or the meaning of a word (sit, eat, sleep). These are basic brain tasks. A child with a serious problem in the area of abstraction wouldn’t have a learning disability or difficulty, but an intellectual disability.

There can, however, be minor problems with abstraction. A person who doesn’t “get” jokes, and doesn’t seem to have a sense of humor, may have a problem with abstraction. A person who doesn’t understand puns or idioms may be having problems with abstraction. Call this person a “pig” and he won’t understand that the word “pig” is not just an animal, but an insult. These types of abstraction issues are exceptions to the rule.

How Does the Brain Learn: Organization

When we think of organization difficulties, it’s easy to imagine a child with a messy room. The child can never find anything. Nothing has a specific place. The child loses things, forgets to bring important items to school, mislays homework, text books, notebooks. These issues may extend to time management. The child is always late and can never turn in assignments on time.

Each of these scenarios: messy room; losing things; forgetfulness; time management issues, have to do with different pathways in the brain. Learning creates new brain pathways. When we call on these brain pathways, electrical impulses light up and activate those parts of the brain.

In some children, the wiring gets crossed or tangled. In other children, the brain pathways may be damaged. Since the circuit in the brain is interrupted, the information never gets to where it is sent, at least not in the form it was intended. Sometimes only part of the information is sent. This leads to incomplete or flawed information processing.

When such processing problems repeat on a regular basis and interfere with the child’s learning, it is time to think whether the child might have a learning difficulty or disability. This is where an evaluation is both necessary and helpful. A thorough evaluation can help pinpoint subtle issues in brain functioning. This can tell parents and educators where the failure is occurring within the three-step procedure of information processing.

That doesn’t mean an exact diagnosis is easy to obtain. A child who calls a fork, a “korf,” may have a problem, but it is difficult to say what the problem might be. It could be the child has a problem with sequencing, verbal output, or auditory processing. The mispronunciation may be about integrating any or all of the these processing areas into one solid whole. For this reason, the child must be assessed in all of these areas.

How Does the Brain Learn: Basic Skills

Whether the problem is sequencing, abstraction, organization, or something else, If a child’s brain has a problem processing information, the child may find it difficult to learn even basic skills such as reading, writing, and arithmetic. When neurological (brain) processing interferes with reading, for instance, the child will be said to have dyslexia. When a processing problem interferes with learning to write, we call it dysgraphia. A problem with processing numbers is called dyscalculia. These are just three examples of learning difficulties that are labeled according to the specific skill sets affected by neurological processing problems.

Learning difficulties are not limited to basic skills. Sometimes processing problems interfere with a child’s higher level skills. Higher level skills include managing time, organization, and abstract thinking. Here too, a learning difficulty is recognized according to the specific processing issue.

How Does the Brain Learn: Four Areas of Processing

A child’s processing problem may have to do with taking in information (input); or it may be about making sense of information (integration). For another child, the difficulty may be storing information and retrieving it for later use (memory). In some cases, a child may have no trouble taking in information, making sense of it, and remembering it, but can’t use this information to form words, write, draw, or gesture (output). It is in one or more of these four basic areas that children diagnosed with learning difficulties will be found to have a processing problem.

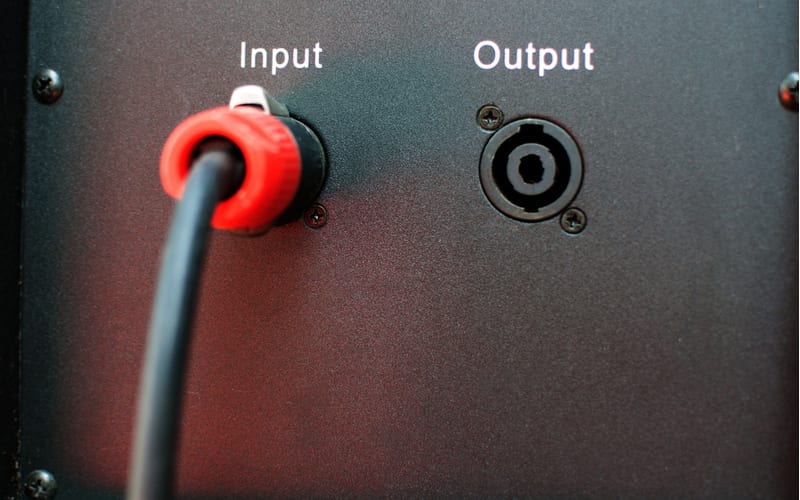

When the brain receives information, this is called input. Sometimes input is visual, or information we understand with our eyes. Sometimes input is auditory, or information we understand with our ears.

How Does the Brain Learn: Visual Input

A difficulty with visual input doesn’t mean, for instance someone who has a vision problem, such as near or far-sightedness. A visual input problem has to do with the way the brain understands what is seen. If the brain sees letters in reverse, for example, this might be a visual input processing problem.

Let’s say a child has trouble with the mechanics of catching a ball. In order to catch the ball, the eyes have to focus on the ball. This is called figure-ground. At the same time, the brain must be able to pinpoint the position of the ball and its path (depth perception). This helps the body understand where and when to move. Finally, the body must obey the brain’s commands, to stretch out the hands and actually catch the ball as it arrives. If the child misjudges the speed of the ball, or how far it must travel, or if the brain doesn’t issue the right commands to the arms and hands, the child may very well fail to catch the ball.

These are just two examples of visual processing problems. In one example, the visual processing problem leads to letter reversals. In the other example, visual processing problems quite literally lead to dropping the ball. There are many other ways we might see the effects of visual processing problems.

How Does the Brain Learn: Auditory Input

Just as a visual processing problem isn’t about being near or far-sighted, a difficulty with auditory input doesn’t mean that someone is, for example, hearing challenged. An auditory processing problem has to do with the way the brain understands what is heard. A child who has an auditory processing problem, may, for instance, be unable to understand how the words too, two, and to are not the same word. This can lead to confusion when the child hears these words in spoken sentences.

In another example of an auditory input processing problem, the child might need more time to understand what is heard. Because of this, the child misses some of what you say because the speed of your speech is too quick for his understanding. This is called an “auditory lag.”

Children can have both visual and auditory processing problems. This might make it difficult for a child to make sense of what is happening when the child receives visual and auditory information at the same time. An example of this could be the student who sees writing on a blackboard while listening to an explanation of those words.

How Does the Brain Learn: Integration

Once input is complete, through visual and/or auditory means, it’s time for the three-step integration process. The brain must put all the information into the right order (sequencing). The brain must be able to understand how to use the information (abstraction). Last of all, the brain must take each piece of information and add it to the whole to make a complete thought. This type of organization of information is the final step in integration. It is what makes integration complete.

How Does the Brain Learn: Memory

At this point, learning is still not complete. Will the brain hold onto the memory for tomorrow’s French test (short-term memory or working memory), or will the child remember that French phrase ten years later (long-term memory) when she visits France as an exchange student? Like abstraction, it is unlikely that your child would have a serious long-term memory disability. Such a problem would not be a learning difficulty, but rather an intellectual disability.

A short-term memory disability, on the other hand, is a real phenomenon. You see it with the child who spends hours memorizing the names of countries on a map for geography class and then forgets everything during the test the next morning. By the same token, the teacher may be very patient in the classroom, explaining how to divide fractions. But when the child pulls out her math homework that night, she cannot remember how to do the work.

How Does the Brain Learn: Output

The final step in learning is actual using the information. This is called output. Output may be verbal, by way of spoken words or language, or motor, which is by way of muscle activity. Motor output includes drawing, writing, and pointing, for example. A child with issues in these areas might have a language disability or a motor disability.

There are two types of language we use to communicate: spontaneous language and demand language. Spontaneous language is where you begin a conversation. You’ve chosen the topic, and had time to think about what you’re going to say. Most children have no problem here.

In demand language, however, someone might ask you a question. You haven’t chosen the subject, thought about your response, or organized your thoughts. You’ve got this split-second to answer the question. For the child with a language disability, this is a tongue-tying situation. The child may ask you to repeat the question, or simply answer, “What?” or “I don’t know.” Some children will respond but the response won’t make any sense—won’t seem to relate to the question.

In motor disabilities, the child may have a problem using the large muscle groups. This is known as a gross motor disability. For other children, it’s hard to perform tasks that requires using many muscles to work together at once. This is called a fine motor disability.

A child with gross motor disabilities may always be tripping over her own feet. She might fall a lot, spill her milk, bump into things, and drop things often. The child will find it hard to learn how to swim or ride a bike.

A child with a fine motor disability may have trouble writing or speaking. The child who has trouble speaking because of a fine motor disability may find it difficult to coordinate all the parts of the mouth, tongue, throat, and face used in speech. Writing, on the other hand, requires coordinating the use of many muscles in the hand at the same time. Children with handwriting problems may write slowly, or have messy handwriting. The child may even find that the writing hand, when writing, develops a cramp.

This should be considered a very broad overview of a complicated subject. For more information, follow the links for deeper reading. If you suspect your child has an information processing problem or learning disability, it’s important to have the child evaluated.