The Montessori Method, developed by Dr. Maria Montessori and put into use for the first time in 1907, is based on the idea of self-education. Rather than sitting still and absorbing lessons taught by a teacher, the child in the Montessori classroom educates himself with the teacher as his guide. In the Montessori classroom, students use hands-on materials and specially prepared classrooms to develop both intellect and character. In Montessori education theory, this type of self-actualization of students is called “normalization.”

The Montessori classroom is suitable in theory for all ages. In practice, however, most Montessori classrooms are serving preschoolers and kindergartners. Preschoolers are the age at which education is still considered optional, a choice. Parents usually must pay for the privilege of providing their children with the rich alternative environment of the private Montessori classroom.

Some 400 public schools in the United States do offer a Montessori education covering kindergarten through high school. In general however, the Montessori Method has a reputation of being experimental or progressive, although at the age of more than one hundred years, it cannot be either. Perhaps the reputation is due then, to the exclusive nature of the Montessori classroom, which is mostly available to children of families with means.

Montessori Method Classroom

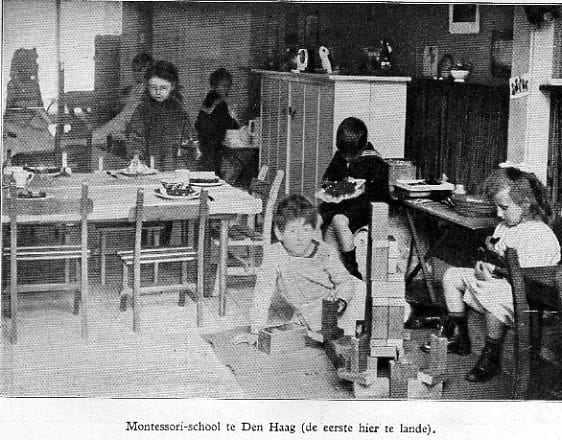

The prepared classroom is a central feature of the Montessori Method. The furnishings and the materials with which the classroom is outfitted are chosen and situated within the room to create a nurturing environment that fosters learning. The furniture will be child-sized and well-made. Learning materials are self-explanatory and teach problem solving and practical skills.

According to Montessori education theory, children have sensitive periods which are conducive to learning specific skills. This can be likened, for instance, to the concept in the traditional classroom (as opposed to the Montessori classroom) of “reading readiness,” in which a child shows specific developmental skills that signal a readiness for learning to read. The Montessori-trained educator is watching for these sensitive periods, which serve to guide the teacher into providing the environment and materials that suit a specific sensitive period.

A key concept in the Montessori Method is respect for the child. In traditional classrooms, children are expected to be quiet, to listen, and sit still. The teacher is a central figure or authority: the vehicle through which lessons are delivered. In the Montessori Method, the child is central to the learning experience. Materials deemed appropriate are provided and the teacher is available for guidance, but education is achieved through the child’s own exploration process.

Many of the materials provided to children in the Montessori classroom, have what is known as a built in “control of error.” The errors become evident to the child through his exploration of the materials. For instance, in fitting a set of pegs into a set of holes, the child will see that while a small peg will fit into a large hole, he may end up with empty pegs and holes unless he places the small peg into the hole that is just the right size for it. If all pegs are placed correctly, on the other hand, there will be no leftover pegs.

In this way, the child not only learns about shapes and sizes with no instruction from an authority figure, he experiences the lesson in a hands-on, active manner, which helps to cement the knowledge he gleans into his long-term memory bank. This is in contrast to, for instance, cramming for a French exam. The student may study long into the night, the night before the exam, and get an excellent grade as a result. But the words and phrases learned as the result of cramming will not be retained long-term.

In addition to acquiring lasting, long-term knowledge, the Montessori Method fosters independence. The child doesn’t need a teacher to point out his errors. The errors are self-evident. This is distinct from the typical classroom in which the child is completely dependent upon the teacher for the acquisition of knowledge and correction of mistakes.

This is not to say that the children in a Montessori classroom are abandoned to their own devices. Rather, the operative principle guiding the Montessori classroom is “freedom within limits.” Teachers are trained to encourage children to find the answers on their own. Active self-directed learning periods are balanced with collaborative learning sessions and learning sessions taught by peers.

The classrooms are not divided by age, but will have students of various ages within the same classroom. Older, more advanced students are encouraged to mentor younger, less experienced children. In this way, children can try on leadership roles, while younger children learn to respect the accomplishments of their peers.

Abstract Thinking

As children mature, abstract thinking becomes more central to the learning process. Students may study in groups to solve problems through discussion. Research and technology begin to figure large in the educational process, as do writing skills. Field trips are prized for the ability to continue the hands-on learning of the earlier years. Such trips may extend for several days at a time.

Careful preparation is one of the hallmarks of the Montessori Method and this can be seen in the execution of projects, experiments, and presentations by older students, which may take long planning and a great deal of time. The students set daily and weekly goals toward completing their curriculum work. Respect for the individual, taking responsibility, and development of character are built into study units as important core values for students.

High school students may volunteer within the community or take a real-life business internship to foster leadership skills, teamwork, and independence. Students may run their own businesses to learn the practical application of skills they have learned in the classroom and during their internships. The social side of a teenager’s life is not excluded. There may be dances, social evenings, plays, dances, or movies as part of the student curriculum.

The Montessori Method has found fertile soil in the U.S., with Dr. Montessori’s original vision being played out in thousands of schools across the country. The American Montessori Society has its headquarters in New York City, has more than 10,000 members, and offers 92 education programs for teachers seeking accreditation in the Montessori Method.