Genes and Motivation: Why Doesn’t My Child Care About His Grades?

“Why doesn’t my child care about his grades,” is a familiar, if unspoken refrain for many mothers. They think of it when they see a less than stellar report card. They think of it when they see their kids messing around on their iPads instead of doing their homework. And most of all, they think of it after yet another meeting or phone call with a teacher at her wit’s end: “He’s bright, but he just doesn’t seem to care. He doesn’t realize how this will affect his future.”

Of course, if you were kind of that way yourself when YOU were a kid, you may wonder whether this is a mere coincidence or something in the way you raised your child. But you probably never suspected it was something genetic. Because the idea that a kid could inherit a lack of motivation–that there’s a connection between genes and motivation?? Well, that’s just too weird.

Genes And Motivation?

Except: a new study suggests that genes are at least part of the reason that some kids just could care less about their academic performance. If that surprises you, you’re in good company. Co-author of the study in question, Stephen Petrill, was also surprised. He went into the research trial, assuming that environment (the school, a child’s teacher, the family/home), would probably be the most significant factor in a child’s lack of desire to study. The results of the study, which will appear in the July 2015 issue of Personality and Individual Differences, proved Petrill wrong.

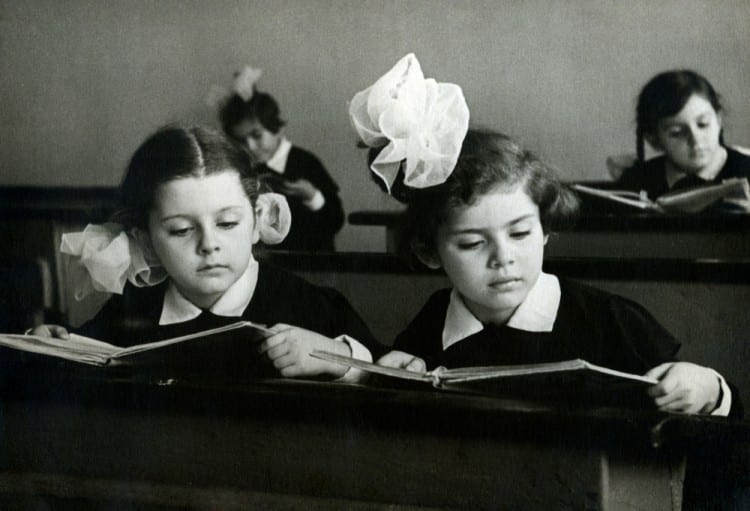

The study was based on data pulled from six separate studies performed in the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, Germany, Russia, and the United States. The participants numbered over 13,000, all of them twins aged 9-16. While each study used slightly different methods and questions, the concepts measured were similar.

What the scientists found was that anywhere from 40-50% of the differences in students’ motivation to learn could be linked to inherited genetic characteristics from their parents. The second most important part of a child’s learning motivation was a non-shared environmental factor, such as twins in different schools or classrooms, for instance.

Petrill, a professor of psychology at Ohio State University said, “We had pretty consistent findings across these different countries with their different educational systems and different cultures. It was surprising.”

It may be natural for the teacher to blame the student’s lack of motivation on the parents, while the parents may tend to blame the teacher for not inspiring their children to learn. And of course, teachers and parents may even blame the children themselves for just not trying. “The knee-jerk reaction is to say someone is not properly motivating the student, or the child himself is responsible,” says Petrill.

“We found that there are personality differences that people inherit that have a major impact on motivation. That doesn’t mean we don’t try to encourage and inspire students, but we have to deal with the reality of why they’re different.”

The study participants rated how much they enjoyed specific learning activities. For instance, in Germany, the students were asked to assess how much they liked reading, writing, and spelling.

All the students were asked to evaluate their personal abilities in the various school subjects. In the United States, for example, students were asked to say how much they agreed with statements such as, “I know that I will do well in reading next year.”

The researchers compared how well the answers of fraternal twins matched, compared to the answers of identical twins. Fraternal twins generally share half of their inherited genes, while identical twins share all their inherited genes. The fact that the answers of identical twins were more closely matched compared to the answers of the fraternal twins, bears out the implication that the genetic effect has a stronger impact than other factors, when it comes to learning and motivation.

According to Petrill, the results of the six studies bore a striking similarity, despite the fact that the children were from six different countries with six vastly different cultures. While plain old DNA explained 40-50% of the apparent differences in motivation between twins, approximately the same percentage could be explained by the twins’ non-shared environments. This means that one twin had a different parent or teacher, for instance, than the other twin. Only 3% of the lack of motivation could realistically be attributed to the twins’ shared environments, such as sharing the same family experience.

“Most personality variables have a genetic component, but to have nearly no shared environment component is unexpected,” Petrill said. “But it was consistent across all six countries.”

Petrill points out that this doesn’t mean there is a gene that determines how much a child will enjoy learning, but the findings do tell us that genes and the environment do shape a child’s thirst (or lack of thirst) for learning.

“We should absolutely encourage students and motivate them in the classroom. But these findings suggest the mechanisms for how we do that may be more complicated than we had previously thought,” he said.

Altogether, Petrill had 25 co-authors, while the lead author was Yulia Kovas, a Goldsmiths, University of London professor of psychology. Partial support for the study came from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development.