Dyslexia (that catch-all term for reading difficulties) tends to take us by surprise. We’re surprised when a child is diagnosed with dyslexia or when we meet an adult who is unable to read. We’re taken aback because we think of reading as a skill learned in grade school. Reading is, to most of us, something as basic as walking, talking, or breathing.

If you were to think about reading and what it involves however, you might instead find yourself astonished that anyone can learn to read at all. The act of reading, when broken down into parts is about seeing a symbol, remembering it when you see it, associating that symbol with a sound (or sounds, depending on context), and knowing how to either think the sound, or make the sound with your tongue, mouth, and breath. That’s a lot of steps to go through to get from point A to point B.

Somehow, most of us manage to do this incredible feat of magic and become fluent in reading by the end of third grade. A significant number of us, however, do not. This can happen for a variety of reasons. Even dyslexia experts do not agree on the reasons for reading difficulties or what can or should be done to improve the reading skills of someone with dyslexia.

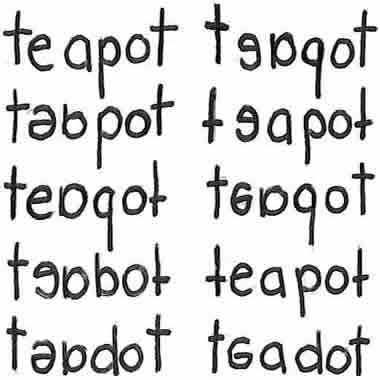

Dyslexia shows itself in all sorts of ways. For some people, the letters m and n look exactly the same. For others, the letters b and d look the same. Lacking the ability to distinguish between two similar letters is by no means the only way that dyslexia presents.

Dyslexia As Reading Difference

Some people with dyslexia look at a page of text and see letters jumping or moving around the page. Imagine trying to read a word when the letters won’t hold still on the page! Others with dyslexia may be confused by the white spaces between letters and words. They may not be able to see where one letter starts and another one begins. Or they may see irregular patches of white separating blocks of text in a way that was never intended by the author or printer.

People with dyslexia may be able to read some letter fonts but not others. Or they may be able to read if the letters and the page they are on are not black and white, but in specific colors that make reading easier for them. Some people with reading difficulties may find it easier to read when the letters are enlarged.

Dyslexia, in other words, is not a single reading difficulty, but a “wastebasket term” connoting any and all reading difficulties of which there are many.

Reading difficulties are not new. The phenomenon was first identified by a German physician, Oswald Berkhan, in 1881. The term “dyslexia” was coined by an ophthalmologist—also German—Rudolf Berlin, who put together the Greek word “dys” (abnormal, bad, or difficult), with “lexis” meaning “word.” The contemporary definition of dyslexia, put into words, is an unexpected difficulty in reading irrespective of age, intelligence, education, or motivation.

As difficult as it is to put a single definition on dyslexia, it’s even more difficult to estimate how many people struggle with reading. Worldwide, it is estimated that 10% of the population has dyslexia. That means that one in every ten people has the reading difficulty. It may help to put this figure into perspective when one compares it to the 1 in 600 people who have Down syndrome, the 2 in every 1,000 people who have cerebral palsy, and the 5 out of every 1,000 people who have epilepsy.

Dyslexia As Reading Difficulty

The definition of dyslexia as a reading “difficulty” as opposed to a reading “disability” offers us a way to better understand the most noticeable feature of dyslexia: a difficulty in acquiring reading skills. To gain a deeper understanding of dyslexia, however, it is important to stress that reading difficulties are caused by many processes and factors that may also affect a person with dyslexia in areas other than reading.

The various ways dyslexia is expressed suggest that reading fluency is based on multiple skills, abilities, and brain functions. Consider the fact that scientists have yet to discover a reading center in the brain. The brain is wired to permit speech, movement, vision, hearing, and a variety of other skills, but if a specific area of the brain has evolved to handle reading tasks, scientists have not found evidence of its existence.

Instead, the brain must call up numerous resources that all play a part in the act of reading. As the individual reads, various brain functions or skills are called upon and each one has some connection to the reading process. At the same time, none of these skills are specific to reading. This is very different than, say, the process of vision, for which the brain has developed a specific neural (brain) system dedicated to a single process: the process of vision.

Since dyslexia results from differences in various brain functions, it is logical that people with dyslexia will have other learning difficulties. Those with dyslexia may have trouble with spelling, organization, carrying out instructions, and distinguishing right from left. These manifestations of brain function differences may not be apparent until a child is school age or older.

On starting school, the child may experience failure in the classroom without understanding why this is so, never having been in a like situation before. As the child accumulates failures in the classroom, there may be a loss of confidence, poor self-esteem, and great frustration. The result of these feelings may be a reluctance to attend school.

Many adults with dyslexia can recall the shame they experienced as children in elementary school, for having reading and other difficulties. It’s an emotional scar that never quite heals. This makes early and accurate diagnosis of reading difficulties crucial to a child’s social and emotional, as well as academic welfare.

The school sometimes takes a role in making sure children with reading difficulties are tested. More likely, parents will need to consult with an educational psychologist. This means that getting a child tested and diagnosed with dyslexia can be an expensive undertaking.

Dyslexia Is Not An Intellectual Disability

While experts are still puzzling out the exact causes of dyslexia, there is a consensus that dyslexia is not an intellectual disability. It is important to convey to a child with dyslexia that a reading difficulty has nothing to do with intelligence. You might explain dyslexia to your child by comparing a reading difficulty with colorblindness. Colorblind people are of normal intelligence and gifts. So are people with dyslexia. They just see things differently than others.

If your child should be diagnosed with dyslexia, you may worry about your child’s academic performance and future. Today, however, there are proven  methods for helping the child with dyslexia span the gap between areas of difficulty and learning.

methods for helping the child with dyslexia span the gap between areas of difficulty and learning.

The main thing to remember is that dyslexia is not a disease. It not only cannot be cured, but there is no reason to think that a cure is necessary. Dyslexia comes to people who have unique sorts of minds that have their own strengths and weaknesses. Some people, in fact, refer to “the gift of dyslexia.”

A Canadian woman, Karen Hope, who runs a website called Dyslexia Victoria Online, wants people to think of dyslexia as a “learning difference” as opposed to a “learning disability.” Hope sees dyslexia as a learning style that is right-brained, and the traditional education approach of most schools as left-brained. Most people learn to read by dint of the left brain which builds on a series of steps that help the reader to translate symbols into sounds.

Children with dyslexia, on the other hand, see the world with the right brain. Such children are “strong spatial thinkers,” according to Hope, and they see things in great detail, through images and storylines, rather than through letter symbols and abstract concepts. Hope says this knowledge should be used to help children with dyslexia succeed in their learning and in life skills in general.

A parent might, for instance, tell his child to clean her room, and the child will know what to do. The child with dyslexia, on the other hand, has difficulty understanding the phrase “clean up your room” because it is a fairly abstract command. A parent should, instead, offer the child with dyslexia, specific instructions. You might, for instance, tell a child with dyslexia, to hang up her clothes, make her bed, and put her books back on the book shelf.

The same technique works well in the classroom, too. Children with dyslexia will need lots of direction in order to understand what it is they are meant to do in class. The more complete the directions, the better the child’s academic performance, from this perspective. A good rule of thumb for the teacher to adopt in teaching children with dyslexia is to offer detailed instruction.

Much research remains to be done to further our understanding of dyslexia. But in the last decade, tremendous strides have been made by the researchers dedicated to this field of study. As each new piece of the dyslexia puzzle is found, people with dyslexia everywhere are closer than ever to improved function and living fuller, more satisfying lives.

Ms. Epstein,

About 15 years ago, NIH-funded research was done in Florida that showed that over 95% of children showing signs of weak pre-reading skills could be kept from experiencing severe reading difficulties in the future when they were given proper instruction at the proper frequency. Another study, also funded by the NIH, showed that older children (about 3rd grade) who were already experiencing reading difficulties could see dramatic improvement in their reading skills in a relatively short period of time. The methods used in those programs have since been used to help thousands of children overcome their reading, writing, and other language skill weaknesses in clinical and classroom settings. The problem with most classroom reading instruction is that it assumes skills that almost 20% of children have not fully developed due to dyslexia and other language processing difficulties. Going back and strengthening foundational language skills allows sets children on a more natural developmental course. I would be happy to share this research with you if you email me at info@nowprograms.com. The more people know about it, the more likely these methods are to be used to help more children.

Hi Stephen,

I just sent you a note requesting to see the research you mention. Thanks for dropping by and reading the blog!