Can trauma today hurt our grandchildren at some distant point in the future? It seems so. A new study just published in the latest issue of Pediatrics tells us that the greater the impact of trauma or violence in the home, the greater the risk that one’s children will show the scars all the way down to their DNA. The study, performed by researchers from the Tulane University School of Medicine, concludes that children in homes impacted by suicide, domestic violence, or a family member in prison have telomeres that are substantially shorter than would be found in children raised in more stable homes.

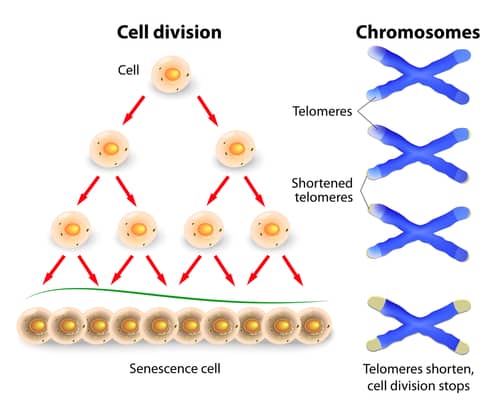

Telomeres protect the chromosomes from shrinking and deterioration. Some have compared telomeres to the protective plastic sheathing on the ends of shoelaces which serve to prevent shoelaces from unraveling. Seen in this light, telomeres serve as cellular markers for the aging process. Shorter telomeres equal a shortened lifespan and are considered to heighten the risk factor for such diseases as heart disease and diabetes while contributing as well to the risk for cognitive decline, mental illness, obesity, and general poor health in adulthood.

Researchers at Tulane’s Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental Genetics Laboratory, under the direction of laboratory director Dr. Stacy Drury, obtained genetic samples from 80 New Orleans children aged 5-15, and spoke to their parents about their environments in the home and with regard to traumatic life incidents and adversity. Dr. Drury, who served as lead author on the study said, “Family-level stressors, such as witnessing a family member get hurt, created an environment that affected the DNA within the cells of the children. The greater the number of exposures these kids had in life, the shorter their telomeres were—and this was after controlling for many other factors, including socioeconomic status, maternal education, parental age and the child’s age.”

Drury’s team discovered that gender influenced the way in which trauma influenced the children’s DNA. Trauma appeared to have a more severe impact on young girls, as evidenced by the higher rate of shortened telomeres in girls as compared to boys in subjects having experienced traumatic family life events. There was, on the other hand, a surprise finding that boys benefited from a mother’s higher level of education which was found to have a protective effect on telomere length, alas only in boys until the age of 10 years.

Drury believes the study results suggest that mediating the home environment could mitigate the biological effects of adversity on children.

Now for a personal note. I researched this piece because I wondered what might be the effect of a recent kidnapping in my community on my children. I was distressed to read about this study, because to me, the results suggest that the terrible events in my region might be shortening the lives of my children and grandchildren, since the damage to DNA is passed on to subsequent generations.

It is interesting to me on a sociological level: do violent societies die out in part because of damaged DNA? This is both alarming and reassuring to me. Violent terrorists and abusive spouses and parents are theoretically serving to kill off their own offspring, leaving the world to those healthier in both mind and body. Long life is deeded only to those who manage to raise children in a stable home environment.

That doesn’t mean that only criminals scar their offspring’s DNA, of course. An innocent person caught in a tragic situation—think Boston Marathon Bombing—has no choice in the matter: they become a party to violence in spite of their own normal, peaceful natures. That cuts me deep as a parent. I can’t always protect my children and their long-term health because of events perpetrated by those outside of my control. I can’t protect my children from the knowledge that three teenage boys were kidnapped by terrorists within walking distance of our home.

This fact also has me thinking about my children’s marriage prospects, as strange as that may sound. Has this kidnapping (and other traumatic events in my community, such as a suicide bombing attempt in our local supermarket, a drive-by terrorist shooting in which a neighbor’s mother was killed, and a shooting at a high school in which a neighbor’s young son was killed) cast suspicion on the DNA of my children and grandchildren, making them less desirable, biologically speaking, as life partners?

My husband would say I think too much.

Maybe so.