The summer is at its midpoint and at many camps, first session is over. If your child returned home a little mopey, you may have to unpack some emotional baggage in addition to his moldy duffle bag. You may also notice some odd behaviors that require a little more patience. Your child might listen to the camp’s collection of campfire songs on repeat. He might eat and sleep for days and days in his camp T-shirt. He may answer your questions with teary, monosyllabic responses. He may seem tired and distant.

Don’t take this behavior personally; it’s not you. It’s him. In the aftermath of after-camp, he’s might be going through “campsickness.”

The first time I went through it was in 1967. I was six. My mom, a single parent, sent me to overnight camp for four weeks on a $300 camp scholarship (Boy, how times have changed.). As a latch-key child, I used to spend a lot of time alone. Overnight camp wasn’t simply a change of venue; it was a magical experience. It was busy, entertaining, and I was surrounded by kids my own age and by adults whose sole job was to care for and nurture campers. Since I was the youngest camper in the entire camp, I got a lot of nurturing. By the end of the session, I didn’t want to leave. I never wanted to leave. And when I did, I sniffled and sobbed for weeks. My mom, unprepared for the storm of emotions, felt rejected and didn’t understand the source of my sadness. Out of desperation, she called the camp office and begged my favorite counselor, Miss Carole (who must be 75 now), to call and console me. Then she promised (wink wink) to send me back the next year.

Thankfully, I did return two more times.

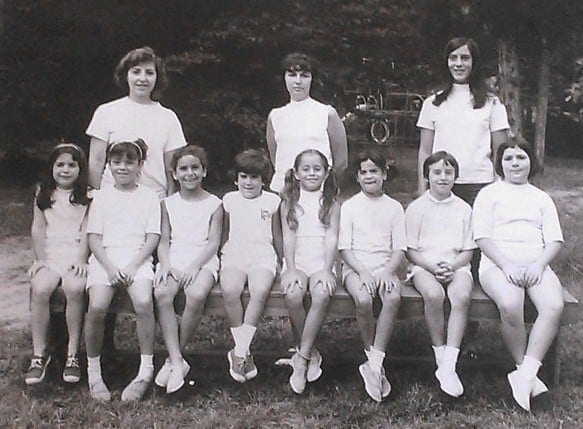

Forty-six years later, I still keep the framed camp photos on my night-stand. I still get those “warm and fuzzies” when I stare at a younger me dressed in picture-day whites with rubber-toed Keds. I get sentimental when dropping off my own children at overnight camp. I still LOVE the smells of camp—Pine Sol and maple syrup, the feel of denim, Peter, Paul & Mary, hospital corners, daddy long legs, and lightening bugs. But most of all, I still remember the grief I felt after camp, the incapacitating campsickness.

So what exactly is “campsickness?”

In his article, “Unpacking Summer: Camp’s Lease Hath All Too Short a Date,” Stephen Wallace, MSEd, and author explains that campsickness is a sense of grief and loss that a child feels after camp ends. Unlike home, the camp environment fosters a close-knit, family-like setting that feels nonjudgmental and intensely emotional. When a child leaves that setting behind, it’s as though he’s suffered a death. In fact, many of campsick child’s reactions are similar to the stages outlined in the death and dying model proposed by Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

In her research, Dr. Kübler-Ross, author of On Death and Dying, interviewed hundreds of terminally ill patients. Based on their input, Dr. Kübler-Ross outlined a widely accepted model of grief, applicable to a variety of life-experiences where loss is a component. Applied to campsickness, the stages of grief might look something like this:

Denial: Your child can’t admit that camp is actually over. Initially, your child is happy to see you and denies feelings of loss.

Anger: Your child is angry that the feel-good feelings of camp and the friendships he made can’t continue year round.

Bargaining: Your child pleads and promises, “if you send me to camp next summer, I won’t ask you for another thing.” Or, your child proposes a great idea, one that could lift his spirits. He will transfer to a private school where his camp friend attends—two states away. And he can live with his friend’s parents. Never mind that the friend’s parents know nothing of the proposal.

Depression: Cognizant that camp is a mere 11 months away and that he can’t switch schools and nothing will bring back the camp experience, your child drifts into a state of depression. At this point, your child might refuse to shower or change his clothes.

Acceptance: Your child, either through justification or acceptance, begins to move forward. Perhaps he’s making plans with friends or thinking and talking about school.

Wallace does caution parents that campsick children don’t necessarily go through all the stages of grief or that stages occur in any particular order. He recommends that parents know the model so they can better understand the range of emotions their child might have during the after-camp transition.

What can you do to make the transition smoother?

Listen to your child and ask them open-ended questions about his time at camp. Allowing your child to relive the experiences through storytelling can be therapeutic and will send a message to your child that you are interested in him and want to help him feel better.

Allow and encourage your child to connect with friends from home and camp. Recently, I visited a camp in New York where campers in the senior division were given an hour of computer/internet time. Though electrical devices are taboo in most camps, counselors felt this exception helps to reduce the campsickness a teen camper might experience. In high school, peer relationships are paramount; a few days out of the loop from school can be isolating for a child and may affect peer relationships. By encouraging campers to maintain relationships, the camp is helping to anchor kids before and after camp.

Reassure your child that camp will happen again. None of us can know the future. Perhaps your child will want to do something else next summer. In an uncertain economic climate, finances can change. But, your child doesn’t need to know this when he’s campsick. Tell him that camp next summer is always an option, and do what you can to help him through the grief.

http://www.acacamps.org/campmag/1201/unpacking-summer

http://www.ekrfoundation.org/five-stages-of-grief/

http://www.traumaweb.org/content.asp?PageId=48&lang=En